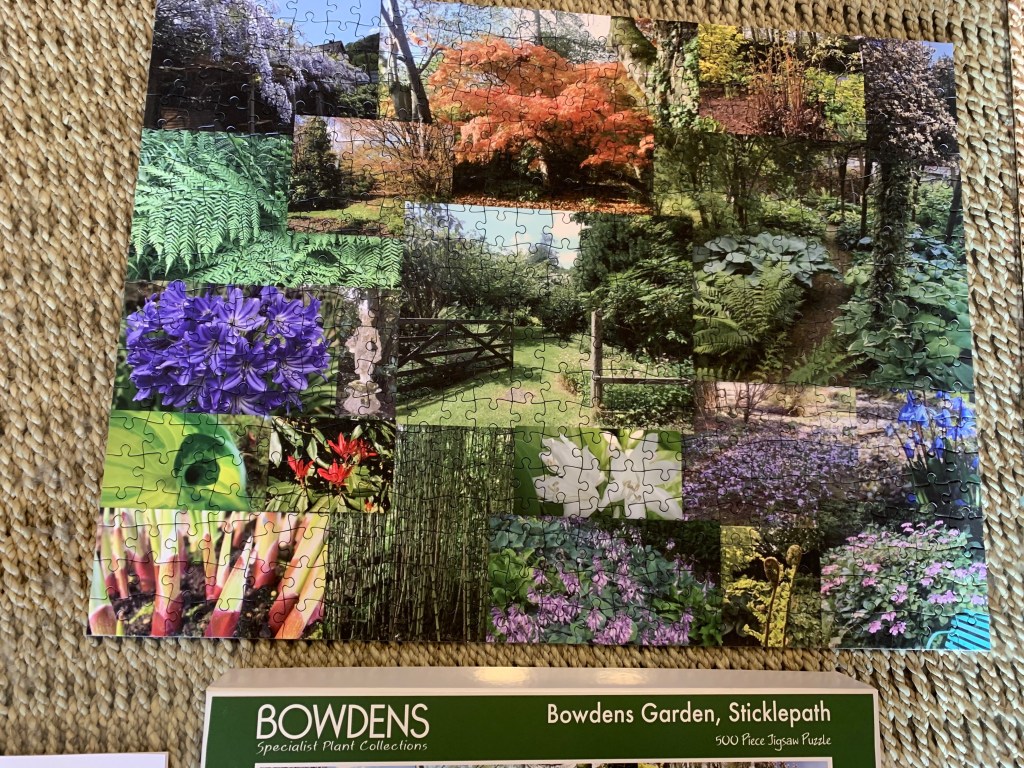

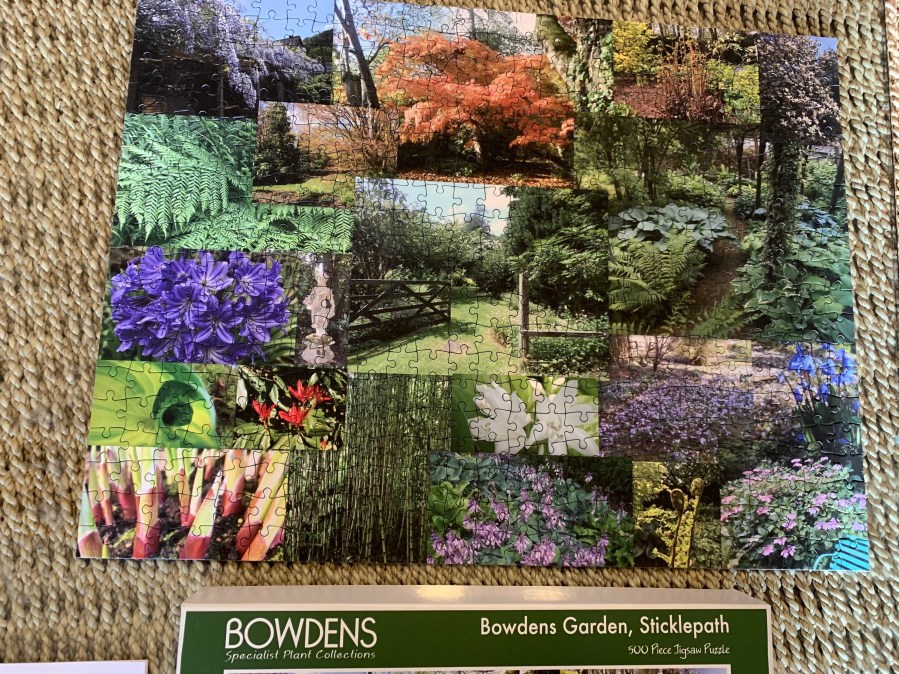

Boxing Day activity – completed today! What is your favourite genealogy or Your Place gift?

Best wishes for the New Year! 2021 is going to be a great one!

Boxing Day activity – completed today! What is your favourite genealogy or Your Place gift?

Best wishes for the New Year! 2021 is going to be a great one!

When I lived in Malawi (2010-12) it became very clear that planning for something eg getting a fire extinguisher to deal with any potential fire, was tantamount to inviting the fire to happen. It was difficult to plan anything in advance. Of course the English think differently – or do we? Why do we find it so difficult to write our Will? I will get around to it…. We might not want to think about our own mortality but Covid has rather brought it to the fore. Unlike a fire which we all hope to avoid, death is inevitable, we just hope it is a way off. In the event, it is so helpful to our relatives or friends if it is clear what should happen to our possessions. Of course this can include making a plan for our family history items.

Soldiers were encouraged to make a Will before going into battle. These can be found on Gov.uk in a separate tab section). Admission to hospital for whatever reason can similarly focus the mind. I updated my Will recently after a change of address, but with any change of circumstances (eg grandchildren or family bereavements) you should consider changing your will or adding a codicil to clarify your wishes. However, the costs if you involve a solicitor are very considerable. Do ask in advance is all I can say!

It was timely therefore when I came across some historic receipts and accounts of the costs surrounding creating and administering wills, which I share with you today. I have also been surprised by how many relatives have made or updated their will in their final weeks. ‘Lucky’ to get warning of their impending doom I suppose. My 2x gt grandmother wrote hers but did not get time to sign it.

Wills can of course be invaluable to the genealogist, giving relationships, married names of daughters, occupations, addresses, an idea of wealth and lifestyle, property owned etc etc etc. It can also help create a timeline of events.

In August 1945 Albany Finch, my great grandfather, became ill and clearly realized his life was at risk. We have an unsigned original copy of his last will and testament dated 22nd August 1945, witnessed by neighbours from Ska View Cottages Margaret R Tucker and Frank Richards. From the will we can learn about all his surviving children. In particular, that his son Alfred James Finch, a clerk, was settled with his family in South America. Albany believed, correctly, that his daughter Phyllis was a civilian internee in Stanley Camp, Hong Kong. There were huge concerns for the safety and well-being of Phyllis who had been serving as a missionary in China and was subsequently interned by the Japanese for the full duration of the war with very little if any communication.

Albany did not live long enough to see the end of the war on 2nd September. He died on 29th August 1945. Phyllis arrived back in England in December. Imagine for her, after the terrible ordeal of a long internment to arrive home only a few weeks after her father died, very sad. It is perhaps only at a time of “lockdown” that we can begin to comprehend the impact of such separations and bereavements, at a time when global communication was far from what is possible today.

There are several other useful sources of information created around a death. The memorial inscription can be informative, perhaps a newspaper obituary, the death certificate, and probate records. Albany’s gravestone mentions his three infant children buried there which we may otherwise not have known about.

The Western Morning News on Tuesday 30 August 1945 said:

“The death took place at Cleave House, Sticklepath yesterday morning of Mr. Albany George Finch. He was in his 82nd year. He was one of the best- known public men in the district, a devoted member of the Methodist Church, and a Liberal. A magistrate, chairman of governors of Okehampton Grammar School, and long-standing member of Okehampton Guardians Committee.” The list of mourners hints at wider family members and friends as well as representatives of organisations he was involved with..

The death was certified by Dr C.J.Sharp. At that time village doctors would have used a microscope to help diagnose illness. He said the cause of death was ‘Leuco-Erythroblastic Anaemia’, a diagnosis based on the microscopic appearance of the blood, one commonly associated with advanced cancer. Albany was buried in Sticklepath with his first wife Mary.

The Death Certificate of Albany George Finch Male Edge Tool Maker aged 81y died 29 August 1945 at Cleave House Sticklepath, Sampford Courtenay R.D. Informant Muriel C. Bowden daughter also of Cleave House Sticklepath near Okehampton. Registered on 30th August 1945.Walter Newcombe Registrar sub-district Tawton I the County of Devon. The Red one penny stamp on the certificate reminds us George VI was king.

Probate was granted 6 Feb 1947 to his two daughters Jessie Emma Barron, widow and Muriel Ching Bowden, wife of Charles and to Ralph Finch Edgetool Manufacturer.

Ralph was his nephew, and right hand man in the business. Albany’s will is largely concerned with the business and what will happen to that. Clearly as the end of the second world war was approaching economic times were hard, rationing was in place. Albany was also aware that the production of tools by hand was becoming outdated, he and his brothers had already diversified considerably. The wording of the will is very gentle in regard to continuing the business if the local relatives want to, and what to do if, or when, they don’t want to. Albany left the proceeds of the business equally to his 4 children. Wills can potentially give a huge amount of information about the situation and family dynamics.

Sometimes, for example if the eldest son has already been given support to set up in business he may be mentioned in the will but appear to be unequally treated. There can be other reasons for an unequal split, for example grand estates tended to go to one person so it would not be split up and lost.

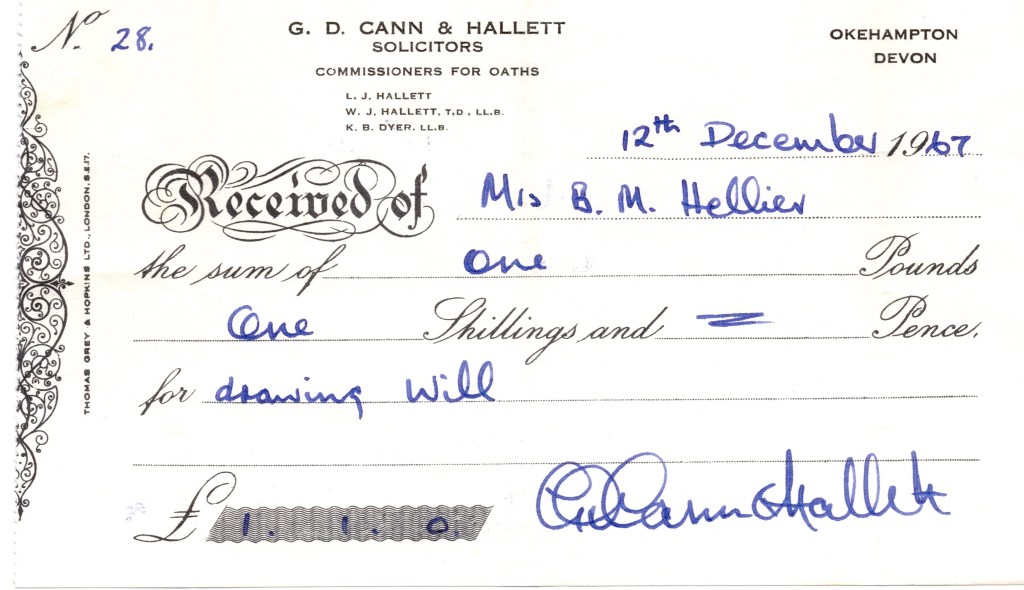

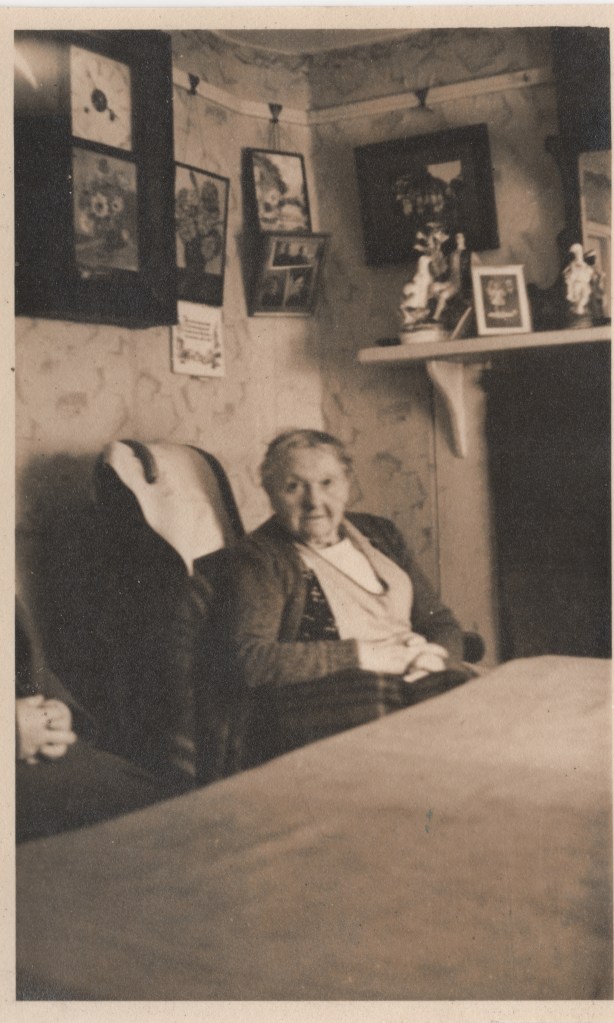

Beatrice Mary Bowden, Mrs William Hellier, who we met in the last post, was more organised – making her will in 1967, 2 weeks before her 87th birthday, at a cost of one pound and a shilling (a Guinea). She lived a further 5 years.

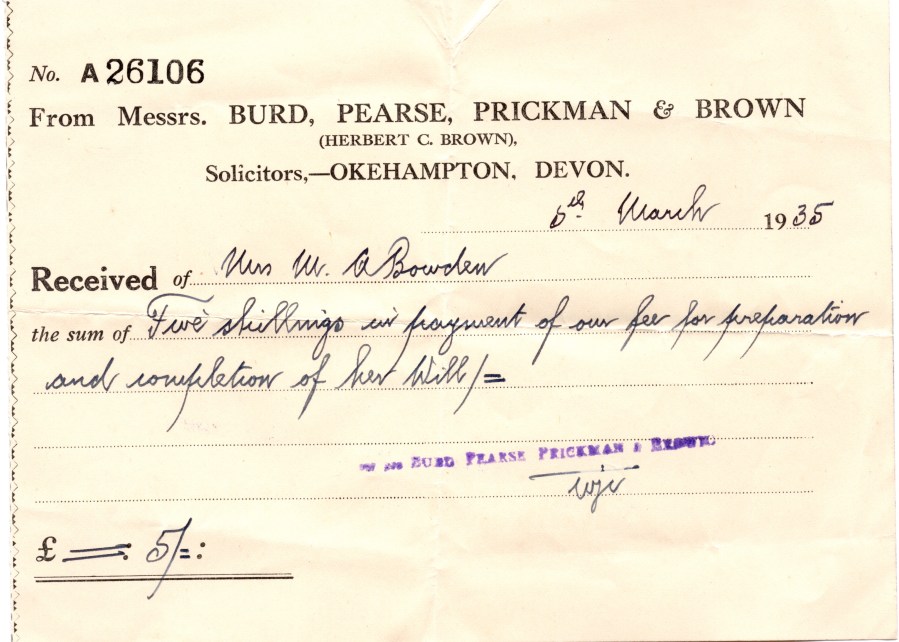

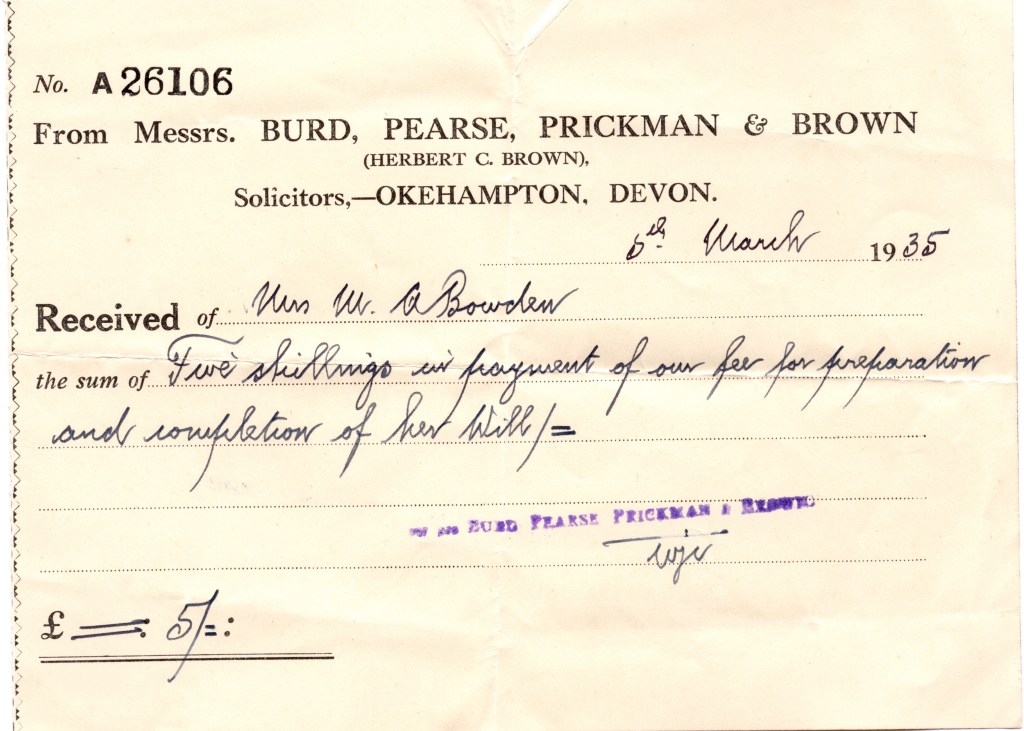

Her mother Mary Ann Bennett, Mrs Emanuel Bowden, born in 1861, was even more organised, making her will in 1935, she continued to live until 1949. Her solicitors charged just 5 shillings (25p).

The executors account for probate outlines other costs associated with the death and administration. In 1972, the year after decimalisation, Redstone’s charged just under £60 for Beatrice’s funeral, with almost £5 additional funeral expenses claimed by the executors. Probate Court fees were £3.30. The solicitor charged £32 including VAT. She left her estate to be divided between surviving siblings.

What a dramatic difference in costs less than 50 years later! Not only that but we no longer pay our dues in stamps, long gone are the threepenny bits and 10 shilling notes of my childhood and £1 notes. Local shops no longer send a monthly bill to regular customers. Cash is hardly used in these Covid times, but in 1972 credit cards were frowned upon by many. (Barclay introduced credit cards 1966 in UK). Debit cards weren’t introduced in UK until 1987. No one in 1972 imagined we would do most of our ‘transactions’ with the wave of a phone, a fingerprint, or click of a computer button!

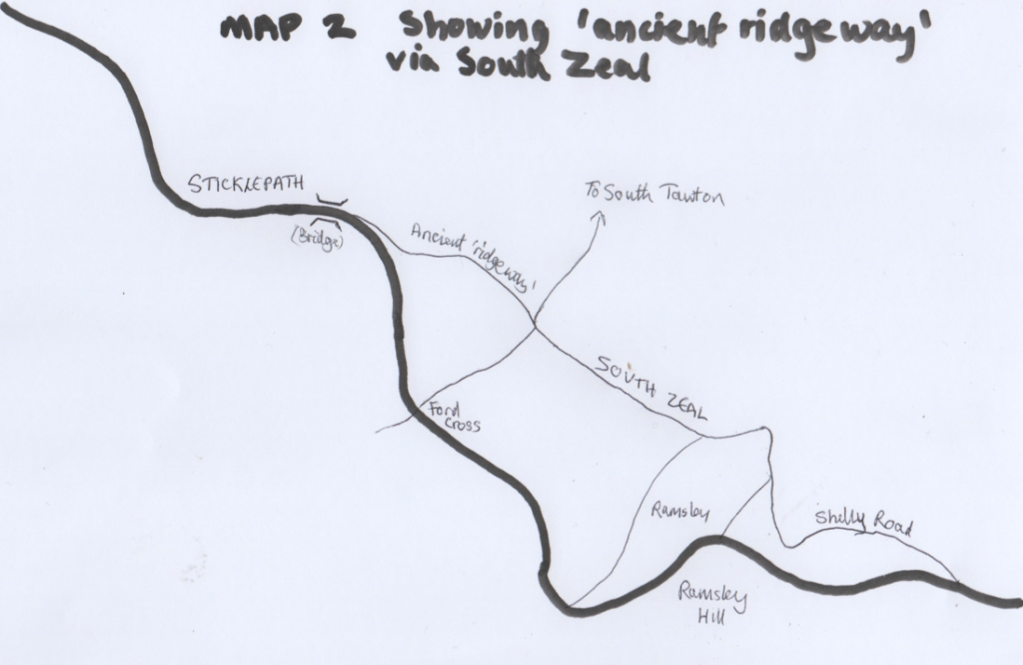

Sticklepath is a very special place on the edge of Dartmoor. My family lived here for more than 200 years. Join me to travel back in time, leaving the comfort of our automobiles as we drive from Exeter towards Cornwall along the old A30 to Sticklepath. Travellers along the ancient ‘ridgeway’ may have had a horse and cart but would mainly be on the ever trusty “Shanks’s pony”, in other words on foot, as they passed through South Zeal to rejoin our route just before Sticklepath Bridge. We follow the less steep road, built in 1830, down the hill past Ramsley Mine with its spoil heap. Many of the workers here came from Sticklepath.

We continue to Ford Cross. In my youth there was a useful garage at Ford Cross, the first place I bought petrol, now houses. Turning left here would take you to Ford Farm (colloquially ‘vord varm’) where mangolds (mangel-worzels) were grown to feed livestock and potatoes for the people.

Entering the village the first dwelling we see is Bridge Cottage on the right. There are more houses now but in 1898 this was the first. Much earlier it was known as ‘Scaw Mill’ and had a separate leat running from the moor to its small water wheel. Now Bridge Cottage and Bridge House are on opposite sides of the road. Before 1830 the main road did not exist and Bridge House holdings came out across to the road at the far side of Bridge Cottage. There were apparently 4 separate households in Bridge House and the adjacent Jane’s Cottage before 1830. Now just one.

Bridge Cottage is isolated on a tongue of land between the two roads. One hundred years ago this was the house of Will and Beat Hellier.

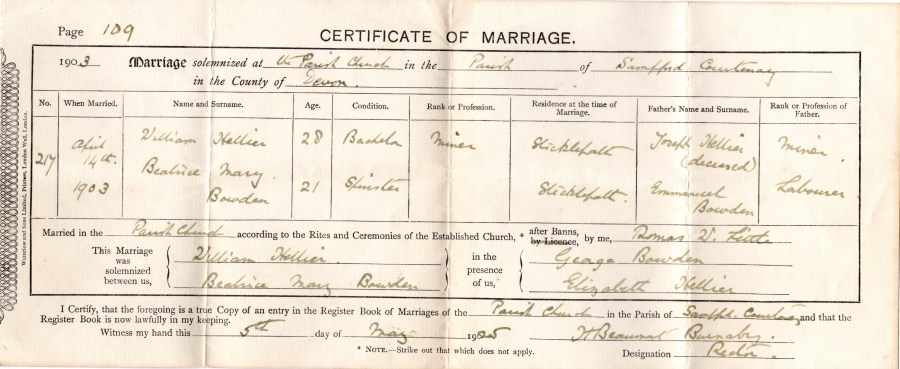

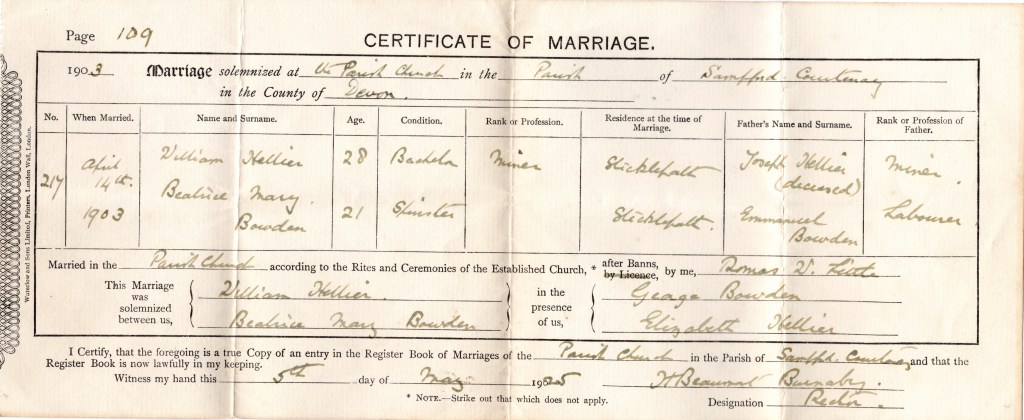

Born in 1876, we find young Willie taking part in Sticklepath entertainments eg in a ‘waxworks’, I presume a tableau, of “Pear’s Soap” (Western Times – Friday 06 April 1888) as part of the evening’s entertainment alongside others providing musical items and shadow theatre. Perhaps his prize winning vegetables in the Sticklepath flower show (eg Exeter and Plymouth Gazette – Friday 15 August 1902) caught Beatrice Mary Bowden’s eye? William Hellier married Beatrice, daughter of Emanuel Bowden, an agricultural labourer who lived from 1843 to 1920, in 1903. Unfortunately no newspaper reports or photographs have yet been found of this event.

Beatrice was the eldest of at least 11 siblings, rather under-estimating her aged on the wedding day (civil birth registration suggests her birthday was 26th December 1880). Charles her youngest brother said they often just had a pan of fried potatoes, perhaps with some onion thrown in, to share for their dinner, and were often left feeling hungry. Beatrice was a live in servant and cook for a gentleman in Sticklepath village prior to her marriage. I suspect she will have supported her wider family and helped make ends meet as a wife, by taking lodgers (suggested by the censuses), and as her mother before her by taking in laundry (especially with a ready water supply in her garden).

William was already working as a stone cutter at the age of 14. By 1911 he calls himself a miner and in 1939 he is a pneumatic driller and quarry heavy worker. He lived his whole life in Sticklepath (1876 – 1947). He was said to be “of a kindly and retiring disposition”.

His obituary also tells us he had been in poor health for a long time. Like many miners and quarrymen he suffered with his chest. Pulmonary conditions like chronic bronchitis were common among them, and smoking may have also contributed to that. His death, from heart failure and chronic bronchitis at the age of 71 years, was certified by Dr C Sharp who lived just across the road in Bridge House.

Living East of Sticklepath Bridge they were in the South Tawton Parish. Those just over the Bridge and the majority of the village were in Sampford Courtenay Parish. This is relevant when looking for birth marriage and death certificates. The funeral took place at St Mary’s Sticklepath (which suggests he was ‘church’ rather than ‘chapel’, and perhaps means he is most likely to be found in Sticklepath burying ground). The newspaper report helpfully names the mourners which includes several sister’s married names.

Although the bridge has been widened they maintained its triangular refuges where pedestrians could avoid the passing dusty carts and carriages and later the muddier speedier cars.

The triangular shape continues below as cutwaters. Walking across the bridge now you hardly hear the Taw River rushing beneath the road for traffic noise. I wonder what it will be like in 20 years time -electric cars self-piloted to reduce speed, noise and accidents perhaps?

Beatrice Mary Bowden outlived her husband by 25 years. In her later years she moved across the bridge into the main part of Sticklepath living in Effra Cottage (now re-named) opposite the Methodist chapel, next to Farley Cottage. She lived with her widowed sister Emily, where their mother Mary Ann had lived. My great Aunts, (Auntie Em and Auntie Beat) still boiled their kettle on a grate over their open fire in the 1960s.

This post is partly based on an assignment done for a #Pharos online course with Dr Janet Few which resulted in a publication (Shields, Helen. Walking Sticklepath through the Centuries: Part 1, Devon Family Historian, vol. 170, (2019) pp.20-25). I hope as my One Place Study progresses to be able to build portfolios for each person or family, not just a list of dates from the census.

Comments and information encouraged – please feel free to comment especially if I have got anything wrong!