Source of information and quotes: HAND-BELL RINGING The living tradition. RINGING FOR GOLD. (Chapter 1) by Peter Fawcett Ed. Philip Bedford. Pub. Donald A. & Philip Bedford 2012

#OnePlaceWednesday #OneplaceStudies #AllAboutThatPlace

Bells remind us of the end of school playtime and perhaps sleigh bells of Christmas. But have you ever tried ringing hand-bells as part of a band or even church tower bells? Have you researched bell-ringing in your place? Here is a short history to start you off.

Hand-bell ringing preceded church bells. The ‘hand-bell set’ was an instrument developed in England in the Middle Ages “from the earlier ‘organic tintinnabula’ (organisation of little bells of different tonal pitches) and the cymbala (9-16 small bells of different tonal pitches suspended on a cross bar).”

Both of these can be found across Europe well before the middle ages and the pien-chung can be found in China very much earlier. Bells strung across a bar could be tapped with a small wooden hammer. The latin ‘cymbala’ can mean cymbals or bells. Indeed the psalm makes more sense to me as:

Praise Him on the big bells (rather than loud cymbals),

Praise Him on the tuneful hand-bells (rather than well tuned cymbals)

Paulinus of Nola (c.354-431) is credited with introducing bells to Christian worship. Large (tower) bells were moved outside the church building itself in the time of Paulinus (Campania, Italy). Inside the church small bells, stringed instruments, likely recorders, as well as small organs began to be used in worship. Tower bells ringing still call people to worship, to ‘look up’ in awe. It is not only Christian worship that uses bells, and they have other cultural links too. The Bayeux Tapestry shows men with hand bells walking alongside Edward the confessor’s coffin to ward off evil spirits.

Parish records may have reference to bells being rung for celebrations, or a muffled peal or half-muffled peal for funerals. Hand-bells may also be mentioned in an inventory, for example, or on purchase perhaps. The earliest record seems to be 1552 St Leonard’s church, Middleton, Lancashire.

Change ringing (patterns rather than tunes) on tower bells and hand-bells began around the early 17th century. Key technical advances from around 1550 made tower change-ringing possible. The full-circle wheel which means a bell can be held upside-down was one. Also critical was development of foundry methods which enabled the tenor bell’s size to be reduced to only about 3 times the weight of treble (higher) bells. This meant the loudness of the bells became more equal enabling rapid runs of notes to be rung. Previously the tenor over-whelmed the volume of higher treble bells which would hardly be noticed alongside the sonorous lower tones. At this time hand-bells were probably still struck with small mallets as the modern clapper mechanism had not been developed.

Bell’s have had a rather bumpy run through history. Most historians are very familiar with Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries and, in his son Edward’s reign, the dissolution of the chantries. Not only did the monarchies make many thousands of pounds from selling off the silver and other ecclesiastical treasures, but also the tower bells.

In 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector and Puritan sensibilities did not allow music in worship. Many more church bells were sold for their metal. However, in some areas records show that the bells were still rung for secular occasions. Bell-ringers though were at risk of being accused of being Papist. One can imagine hand-bell ringers meeting in secret with leather tied around the bells’ clappers to muffle the sound so no passing Roundhead would hear them!

In 1660 Charles II was crowned and the Stuarts brought back music and dancing. The Peak District village of Castleton in Derbyshire has held an annual ‘Garland’ celebration ever since. In many places the tower-bells had to be re-hung or replaced (creating records!).

Church records may reflect costs for maintenance and repair of the tower bells as well as income made by the ringers. For example Wallasay St Mary 1658 onwards include items such as new ropes, repairs to the bells, ‘oyle’ and ‘liquour’ to grease the bells and ‘skins’ to hang the clappers, a

“plank for wheel spokes and a pese to mend ye frame”

Transporting tower bells was very expensive and itinerant founders (some being Henry VIII’s displaced monks) travelled around knocking on vicarage doors looking for work or plying their trade at local fairs. Using charcoal and clay or fire-bricks they would cast or re-cast bells on site. By the mid-16th century a revolution in techniques allowed sets of handbells, each with a leather handle, independent of a frame, to be made.

Technical developments include the use of a tuning lathe, perhaps as early as 1738 by the Whitechapel foundry. Developments in the clapper mechanism too were critical to new ringing techniques.

Hand-bell competitions, especially the Belle Vue contests (from 1855), meant that ringers in the North of England updated their bells frequently to facilitate the best possible sound. The oldest set of hand-bells seems to be held in Stratford upon Avon, cast by the Cor foundry in or before 1727. At Aldbourne foundry in Wiltshire, William Cor (1696-1722) was the first bell founder to cast bells in a sand mould. These bells, before use of the tuning lathe were roughly tuned by filing the outside or inside of the bell.

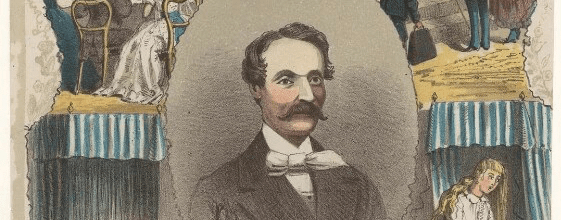

Hand-bells were used to entertain, including in the music hall where George Histon and W.H.Johnson were renowned for ringing ten bells each, 4 in each hand and one on each foot.

When Handel came to England (c.1740) he heard hand-bells often when he was invited to different houses, as well as church bells, so he named Britain “The Ringing Isle”. Bells were also used on draft horses to warn people they were coming, perhaps ringing a chord comprising 4 bells making a distinctive sound for each cart, announcing their presence. (Comparable to ice cream jingles!) Whilst hand bells could be practiced in the bell tower, other bands preferred the local hostelry, perhaps explaining how some were named ‘The Ring O’ Bells’.

There are different techniques for ringing handbells. One bell in each hand came first. Then “4 in hand” where each hand holds two bells with the clappers set at right angles so each bell can be rung independently, by altering the direction the hand is moved. (Presumably the music hall artistes damped their 4 bells so they only rang in one direction, usually bells ring on both strokes of the clapper). Off the table, and Yorkshire method are the other main techniques. Larger bells initially stood on the table. Later the Yorkshire method included lying bells on their side on the padded table enabling a ringer to play many more than 4 bells within one piece.

Note there were no brass bands in these early days, as the valve, so critical to tuneful playing, was not invented until 1815. The emergence of brass bands was probably a major factor in the demise of handbell ringing. However, it is still an art practiced today across the country. Tower bells too – for the Queen’s jubilee it is estimated over 90% of tower bells were rung in her honour.

Do you have, or have you ever had, hand-bell ringers or tower bells in your One-Place Study? What is the earliest mention in records? Don’t forget newspapers may mention people were bell-ringers in obituaries, or tower bells rung for celebrations. Hand-bells too may be mentioned if rung at concerts fairs or other events. Some more ideas for research below.

List of towers with 3 or more bells.

Where to research your ringers.